The Cham Towers & Ancient Citadel of Vijaya

Scattered across the central coast and plains of Vietnam are the ruins of the ancient kingdom of Champa. Lasting for over a thousand years, from the early centuries of the first millennium CE, Cham civilization thrived in the lush, fertile valleys and sheltered bays of Central Vietnam. Vijaya, near present-day Quy Nhon, served as the Cham capital for 500 years, from the late 10th century until 1471, when it was finally taken by the Vietnamese from the north.

An Indianized culture, whose religion for most of its existence was Hinduism, the ruins of Cham towers, temples, shrines and cities are a powerful reminder of the rich history of what is now Vietnam. Visiting the historical Cham towers and bare remains of Vijaya is a rewarding day trip from Quy Nhon, on the central coast. In many ways, seeing the remnants of Cham civilization in this region is far more affecting than visiting the more famous ruins of My Son, near Hoi An. While the latter receives thousands of visitors each day, the sites near Quy Nhon are serene and seldom seen. There’s more of a sense of history here than most other historical sites in Vietnam (or in Europe for that matter).

The ruins of the ancient Indianized kingdom of Champa lie strewn across the plains near Quy Nhon

Guide : Cham Tower & Vijaya

There are several Cham sites within easy reach of Quy Nhon. In this guide, I’ve focused on four of them, which can all be visited in one day. The best way to travel between the ruins is by motorbike (or bicycle, if you factor in a lot more time). However, it’s also possible to hire a local taxi from Quy Nhon to take you around the sites, or organize a car and driver through your accommodation. Public transportation isn’t really an option if you want to visit all four locations. I’ve marked the ruins on my map and linked them via a scenic loop, starting and ending in Quy Nhon.

The countryside is pastoral and beautiful, and back-roads criss-cross the region: if you have time, explore some of the smaller lanes. Below, I’ve written a brief introduction to all four sites of historical Cham Tower (including a bit of historical context), followed by a selection of photographs from each of them. If, like me, you have a general interest in history and enjoy wandering through deserted ruins of lost civilizations, with the sense of history hanging heavy in the air, then you’ll enjoy this itinerary. Other Cham sites dot the region, and it’s worth dropping by the Binh Dinh Museum in Quy Nhon for some historical background.

Thap Doi Towers:

Located just 5 minutes northwest of downtown Quy Nhon, these two towers are situated in a pleasant park next to a busy road. The juxtaposition of the ornate ruins, dating from the 12th century, and the honking hulks of giant juggernauts passing by is jarring, but also very representative of 21st century Vietnam. The towers’s arching forms and floral motifs are echoed, to some extent, in the crowns of the long and slender coconut palms and other tropical trees that grow around them. Inside, the towers taper upwards for 20 metres, like giant red brick chimneys, before opening to the sky. Owing to its easy access, Thap Doi (Twin Towers) is by far the most visited of the four sites in this guide. In particular, they’re a popular selfie spot for Vietnamese teens. Early morning is the best time to visit. Entrance is 10,000vnd.

Red brick & tall, narrow archways characterize most of the Cham towers in this region

Restoration of Cham ruins in Vietnam has been mostly sympathetic to the original structures

Banh It Towers:

Hiding in plain sight, Banh It towers are seldom visited despite being easily accessible and in full view of Highway QL1A. Beautifully restored, the four Cham towers here have a powerful presence and a commanding position atop a hill. Nobody is here, just butterflies and the wind, and, inside the towers, the high-pitched calls of bats echoing off the red-brick walls. Down the centuries, the Cham Kingdom was pushed further and further south, due to Chinese and Vietnamese military advancement from the north, and attacks from the Khmer Angkor kingdom from the west. Thus, the Cham towers in Binh Dinh Province are later than those in Quang Nam Province to the north.

The four Cham towers at Banh It, 15km northwest of Quy Nhon, date from the 12th and 13th centuries, when the Cham capital had shifted south to Vijaya after the fall of Indrapura, near Danang. The Banh It towers are wonderfully situated on a breezy hilltop with panoramic views over the cultivated flood plains of the Thi Nai River, with the Truong Son Mountains to the west, and the ocean to the east. It’s easy to understand why this site was chosen as a place of worship. Indeed, as is often the case with ‘holy lands’, this location has continued to be sacred for future inhabitants, long after the Cham (and the Hindu deities whom they worshiped) had declined.

A Buddhist monastery stands at the foot of the hill and a cemetery is scattered over the lower slopes. As with sacred sites across the Mediterranean, it would seem that land, once sanctified, remains holy through the centuries, regardless of what religion is currently dominant in the area. Banh It towers is a place to linger, soaking up the atmosphere. Entrance is 10,000vnd.

The collection of Cham towers at Banh It are clustered on a hilltop surrounded by countryside

Vijaya Citadel & Canh Tien Tower:

Vijaya (also known as Cha Ban and Do Ban) is one of those places with a lot of history, but very little visible signs of it. The Cham capital from the 11th to the 15th centuries, Vijaya was rich and prosperous. It was subject to many besiegements, sackings, and bloody battles. The Khmer and Vietnamese armies all came and conquered, but, as far as I understand, the citadel stood in one form or another, albeit by different names and under the control of different dynasties, until at least the early 19th century.

The site of Vijaya was in Vietnamese hands since 1471, when it was finally captured by emperor Le Thanh Ton, who oversaw the battle in which some 60,000 Cham were killed. Then, during the Tay Son Rebellion, which overthrew the ruling Vietnamese imperial dynasty in the late 18th century, Vijaya was rebuilt as Hoang De Citadel, stronghold of the Tay Son Dynasty in central Vietnam. However, this only lasted a generation, as Hoang De was ultimately taken, retaken, and taken again after several more brutal sieges, by Nguyen Anh, who was to become emperor Gia Long, the first of the Nguyen Dynasty emperors. Very little remains of the once great citadel.

Parts of the original city wall stand, but most of it has been restored. Open excavations reveal some of the original Cham structure, but the majority of what you see today dates from the Nguyen Dynasty, from the 19th century. Still, it’s an atmospheric place to visit and there’s no one else here. I find there’s a certain pathos about Vijaya/Hoang De today: for all the blood that was spilled in order to hold it or defeat it, all the importance and significance it once had, it’s now hardly more than a forgotten field amongst farmland, with the Reunification Express train rattling by several times a day, a few airplanes passing overhead on their descent to Phu Cat Airport, cows munching grass next to stone dragons, and farmers pedaling silently past.

Only a couple of minutes away, Canh Tien tower stands on a gentle rise behind the citadel. Heavily restored, many of the tower’s decorative features appear to by representations of the tropical foliage that dominates lowland Vietnam. As such, (and as with all Cham towers in Vietnam), the architecture fits its natural environment; managing to be both dominant and harmonious. Canh Tien is probably a bit later than the other towers in Binh Dinh, perhaps the 13th-14th centuries. Entrance is 10,000vnd, but there’s often no one at the ticket kiosk.

The site of the ancient citadel of Vijaya, with Canh Tien tower looming above the trees

The citadel of Vijaya/Hoang De is rarely visited: it’s a place of much history but little in the way of ruins.

Phu Loc Tower & others:

The last tower in this ‘Cham loop’ is the least visited but, in many ways, the most exciting. North of Vijaya, a narrow paved lane branches off Highway 1, winding through an increasingly medieval-feeling rural area. It’s still, quiet, and slow in the midday heat; a clutch of bare-torsoed, sinewy men in their 80s gather in the shade of tamarind trees, marking the site of an 18th century event during the Tay Son Rebellion (of which I could not understand the details). They give directions to the Cham tower, whose hilltop ruins are glimpsed every now and then from the road, but always seem to disappear again. The lanes get narrower, passing haystacks drying in the sun and tethered oxen munching lethargically. The lane turns to dirt, leading through a village cemetery, under whispering eucalyptus trees, at the foot of a hill.

Battered stone steps lead up to Phu Loc tower, standing resolutely on the hilltop, as if it were a part of the natural landscape, unmoved by time. In the clearing, the tower casts a welcome shadow in which to sit and admire the view down over the plains, with the ancient capital of Vijaya and Canh Tien tower clearly visible to the south. It’s easy to use your imagination and start piecing together Champa as it might have looked in the 13th century, seen from this hill. The tower itself is big and time-worn. Partially restored, it’s lost none of it’s gravitas. Goats and cows are your only company, and, sadly, trash. There’s no admission fee.

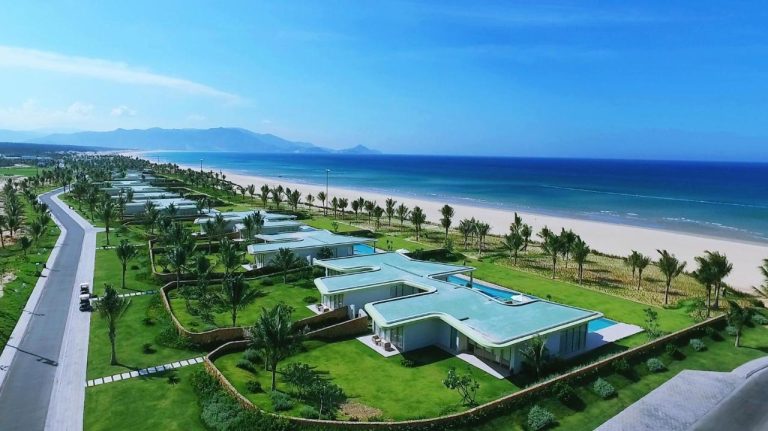

(If you have time, there are several other interesting Cham sites in the vicinity: the triple towers of Duong Long, and the towers of Thu Thien and Binh Lam.) Head back to Quy Nhon via a pretty valley along road QL19B, towards the beautiful beach at Trung Luong. Perhaps stop for cocktails and a swim at the Crown Retreat, before continuing along QL19B down the Phuong Mai Peninsular, over the long, long causeway across the Thi Nai Lagoon (the ancient Cham port), and back into the city.

Phu Loc is the most romantic of the Cham towers: accessed via a steep pathway to a lonely hilltop

Phu Loc tower is large & imposing, its wide base rooted to the ground as if it were part of the landscape.