Mongolia travel blog — Explore the life of Mongolian nomads in the heart of Gobi desert

My English teacher buddy Karen and I plan a Jeep excursion from Ulaanbaatar to the Gobi Desert to learn about the old Mongolian way of life. Ms. Gana, the tour guide, and Mr. Burmaa, the driver, are with us. Gana spends an hour in the store buying food for the journey.

“Grand Caynon” in the ancient desert

Gana fires forth questions about Genghis Khan to us at breakneck speed. For her and the Mongolians, he is the greatest hero and the nation’s father. As a mark of respect, his image is printed on several forms of currency. According to Gana, the Gobi Desert is the region that raised Genghis Khan, allowing him to gloriously conquer territories ranging from Asia to Europe.

The Gobi Desert is one of the world’s five largest deserts and the largest in Asia. Gobi is one of the world’s harshest deserts, stretching 800 kilometers from north to south and roughly 1,600 kilometers from southwest to north east. In the winter, it is enveloped in dense fog, and the mountain peaks are snow-covered. The temperature can dip below -30°C at times. Summer temperatures are higher. The Gobi Desert’s frequent temperature fluctuations, which create several seasons within a single day, are a distinguishing trait, according to Gana.

The clear sky appears to be a great length of blue silk stretched across the heavens, while the sun spreads warm rays to counteract the chill of the desert breeze. We travel to Erdenedalai after spending the day in Ulaanbaatar’s capital, Ulaanbaatar. Erdenedalai is located in southern Mongolia and serves as the entrance to the Gobi Desert. The landscape is a mix of vast meadows and untamed deserts. Gana leads us to a location full of stones hewn from the desert floor and fashioned into various forms, some of which are egg-shaped.

I look at these jutting stones and silently compare them to youngsters from impoverished households since they aren’t as beautiful or famous as Cappadocia in Turkey or the Grand Canyon in the United States. However, it retains the Mongolians’ genuine and honest beauty. The changing meadows create lovely melodies that still echo the footsteps of Genghis Khan’s horse as he went on his conquest journey.

Stone is believed to be an inanimate substance without a soul, yet in the Gobi Desert, their souls are briefly carved on the surface when day gives way to night.

Not only does volcanic activity provide a significant amount of fertile basalt soil for farming, but it also creates magnificent vistas. The term “hoodoo” is frequently used to describe rocks of various forms formed by volcanoes in deserts or hot, dry regions.

“Hoodoos” are often rocks varying in height from a person to a ten-story structure. Hoodoo tops are created by silt and are resistant to erosion, allowing hoodoos to withstand the test of time.

According to geological study, hoodoos are often comprised of thick volcanic rock layers (made up of sticky volcanic ash) whose outer layer is coated with a thin coating of basalt or other volcanic dust from volcanic eruptions. The basalt or volcanic dust layer protects hoodoos from disintegrating due to time or other variables such as rain, wind, light, and temperature. Hoodoos are formed during volcanic eruptions and contain a variety of minerals that produce varied hues depending on the amount of sunlight and the height of the hoodoos.

Gana leads us deep into the deserts of Tsagaansuvarga (Tsagaan Suvarga), Bagagazariinchuluu (Baga Gazriin Chuluu), and Bayanzag, where hoodoos manifest. Karen and I are both captivated as we go around several hoodoos shaped like bamboo shoots, mushrooms, spires of fairy tale castles, or a seated human. They have distinct colors at sunrise and sunset. I’m so taken with them that I don’t notice the chilly gusts of wind that arrive at the jagged cliffs at dusk or morning.

And there are some tiny wells created inside rocks in those mountains. Gana informs us that they contain holy water and invites us to sample some. According to locals, drinking or cleaning one’s eyes with that holy water makes one live a long and healthy life.

Experiencing life in the desert wilderness

Burmaa drives expertly through the vast desert. Karen and I both marvel at how he finds his way through these desolate meadows and sandhills with no signs. People who have lived in the desert for a long time, according to Burmaa, find their way by following the sun and stars. Burmaa, for instance, finds its way by observing the form of the mountains and identifying stone Mongolian monasteries. He can locate a hamlet or town nearby by observing and following the stone temples.

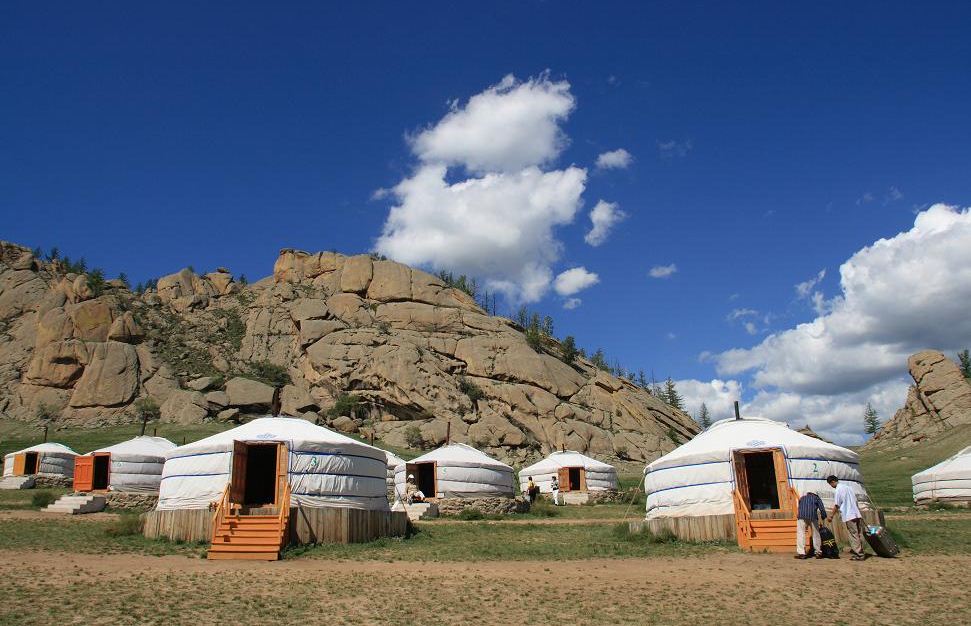

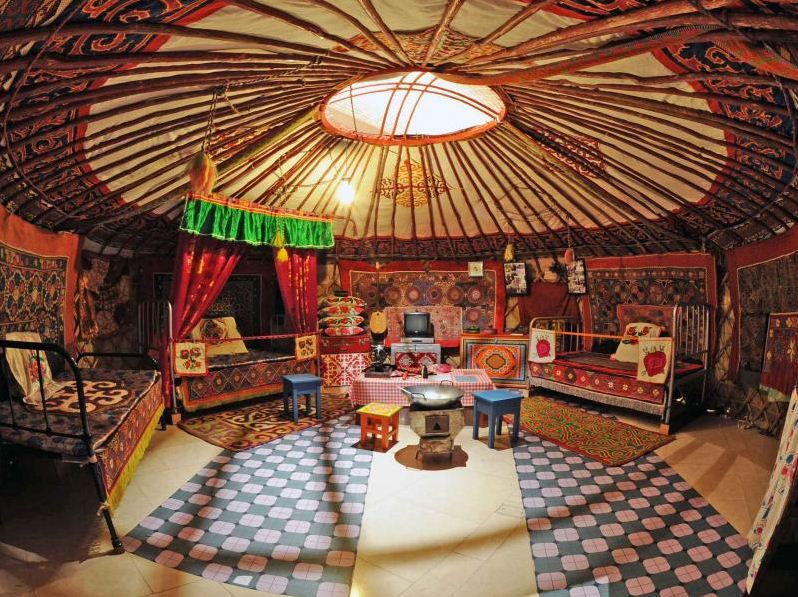

We spend the night in Yurts, which are traditional Mongolian tents. The outside of the tent is simple white, while the interior is vibrantly colored. The majority of everyday activities take place in the host’s main tent; additional tents are for visiting guests. A yurt is separated into two sections: one for the male homeowner, with a bed and a small table on the left, and one for the female homeowner, with a bed and a stove on the right. An ancestor altar is located between the male and female sections. A little table in front of the altar is used for daily activities such as eating or sipping tea. A stove with a large chimney at the entry is used for cooking on a daily basis and also serves as a warmer in the winter.

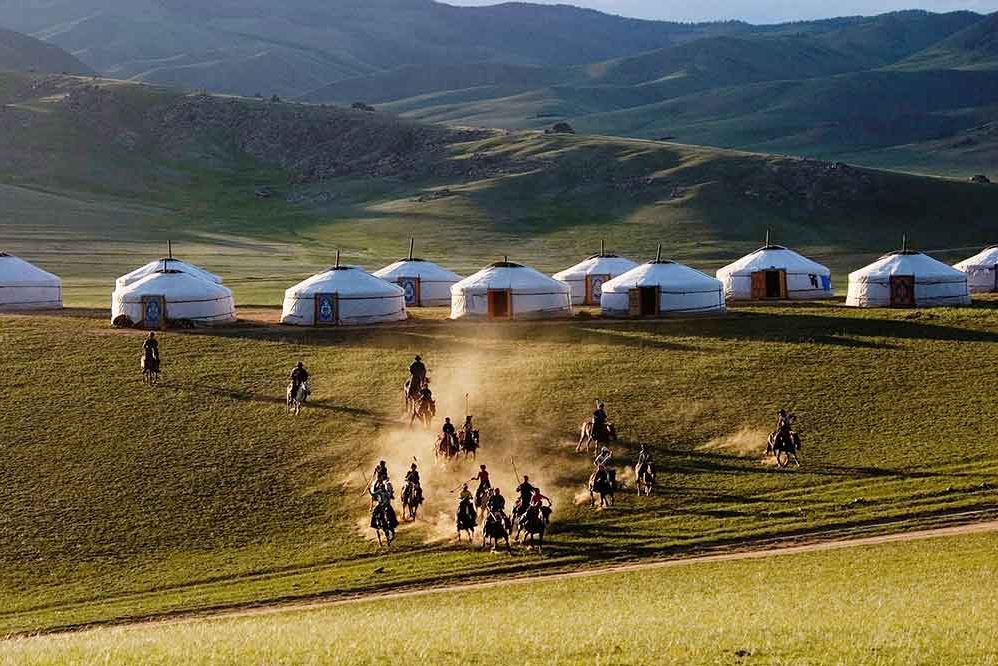

Every afternoon, if Karen and I are not reading books, we shall assist the host in cutting the camels’ hair and fleece. Water and electricity, according to Bataar, a host in Tsagaansuvarga, are two vital components and a source of support for their self-sufficient living in the desert. The typical activity of the locals is to pasture cattle in limitless meadows. When they locate ground water, the locals will abandon their nomadic lifestyle and settle.

Camel hair tangles are plaited and put into felt pieces to form domes or the yurt’s wallboard. Camel hair is used to make sweaters for the winter, while cow excrement is dried and used as fuel to cook and heat. Horses and camels are used to transport water from underground sources to the yurt for storage. Better-off households buy batteries for watching television or lights for drinking tea and talking in the evening. To receive the signal, telephones are strung high on the dome of the Yurt.

I also learned how to wash dishes in a water-saving manner by using several towels after washing once with clean water. Karen has a lot more desert experience than I have. She carries a variety of essential goods with her, like moist tissues for washing her face in the morning, mouthwash, and candles for reading novels at night.

Despite my material limitation, I am grateful for the opportunity to learn about the nomadic lifestyle of Mongolians.

Every experience must come to an end. Living in material scarcity, I still feel happy because I have the chance to become familiar with the nomadic lifestyle of Mongolian people. Personally I think, it was the nomadic lifestyle that helped Genghis Khan to conquer Asia and Europe in the past.

Further information

Two airlines servicing the routes from Saigon or Hanoi to Ulaanbatar are Air China and Korean Air. Korean Air is a good choice with 12 hours for transiting, shorter compared to the22 hours of Air China.

+ The weather in Ulaanbatar is very severe and changeable, a day can have many seasons, so flights need checking before departure.

+ Most of the tourists have to book a tour to go inside Gobi desert. The tour fee depends on the number of tourists. The fee fluctuates from 50USD to 80USD/person/day.

+ Mongolian currency is Tughrik (MNT). Local banks offer currency exchange services with an exchange rate of approximately 1USD = 1.825MNT

+ The capital Ulaanbatar is not so big and tourist destinations are quite close to each other, tourists can walk to visit Ganda Pagoda, Sukhbaatar Square, Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts, International Museum and Bogd Khan’s Summer Palace.